It’s commonplace to see increasing real GDP as a measure of improved utility in society. But it’s less common to imagine an even better scenario of increasing real GDP and deflation. In such a situation, real incomes are increasing in a strong and sustainable fashion, as we’ll show here.

The word ‘deflation’ itself conjures up zero or negative growth. It’s never associated with growth in mainstream economic thinking. Growth is always seen as associated with inflation and even a lack of growth is usually associate with some inflation, in a situation termed as ‘stagflation’.

Can growth and deflation occur together? Do we need to think about ‘GrowthDeflation’?

Casual Economics provides the theoretical foundation for this being a natural situation.

Economies grow in the long-term due to improved technology in the broadest sense–computing, automation and even processes. Technology improvements lower prices over time, as is observed today in the IT sector. Prices can also change in various sectors due to changes in relative demand. This trend will raise average prices in some sectors and lower them in others. These real economic drivers differ from the inflation we see in our economy today. The latter is entirely a monetary phenomenon, based on central banks exogenously issuing new money when there are no real strains on the velocity of circulation. Since funds are created electronically in modern economies, there is no underlying need to issue money to ‘lubricate’ activity.

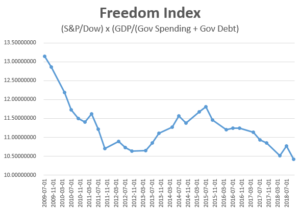

The current model of central banks constantly issuing new funds is a dangerous long-term fallacy. It is truly nothing more than a long-term tax on the asset-poor middle and lower classes, shifting wealth to the asset-rich wealthy. It allows governments to make promises beyond their means and print money to achieve goals without paying any price in the short-term. In the long-term, their currencies and true wealth will be eroded, but in the short-term associated with government election terms low, positive inflation pays off.

Causal Economics shows us that inflation increases benefits for those involved in the central banking process and those with significant assets, while also increasing costs for those without significant assets in the economy.

Why is it worth attention to debate about low inflation? How bad can it be? We should give the issue our attention, because accepting inflation of any sort reinforces a distraction from the underlying means of real economic growth–technological advances.

Naysayers of this analysis will point to historical instances of ‘tight money’ choking off credit. The reality is that tight money is always a reaction to situations where inflation got out of control, situations where real growth wasn’t occurring and money was too loose. Tight money is either the policy correction or market correction to such an out of hand situation, to bring risk levels back in line. Sustainable credit conditions are based on risk/return underwriting, not the level of money supply, loose or tight.

Some might say this post is a brief treatment of a complex topic. We believe it is a case of getting to the bottom line in a straightforward manner, by keeping top of mind the principle of coupled cost and benefits, as shown through Causal Economics.

Should we be aiming for some ‘GrowthDeflation” soon?